Where in Law are Doughnuts?

- Susan Shaw

- May 29, 2017

- 7 min read

Updated: Jun 5, 2023

It's time for new thinking and approaches beyond merely a new Act of Parliament (as some election manifestos suggest) to address the fall-out from Brexit.

Earlier this month, Kate Raworth – the Oxford-based economist – released her much-awaited and aptly titled book “Doughnut Economics”. For those of us specialising in international environmental law and policy and who advocate the central importance of multi-disciplinary thinking for the challenges of the Anthropocene, Kate’s fresh approach creates a sense of hope for the future – and certainly gets the grey-matter working.

From the early Ted-talk days, Kate’s work has now captured the attention of world-leading decision-makers, including this week the World Bank – with one of its Senior Economists, Chico Ferreira, reported as saying “I started this book determined to hate it and found myself really enjoying it”.

Already having earned its place as an amazon best-seller, Kate’s work illustrates that we need a new economic paradigm if we are to successfully ‘bend the curve’ and transition to societies within Planetary Boundaries: that is, the very limits of the Earth System itself (Rockström et al). It begins to then answer the question of how societies can design economic systems that support the soon to be 9 Billion people on our planet within this ‘safe operating space’ identified for a number of years now by Planetary Boundary scientists.

This is now demonstrated to be an eminently achievable task. But we should nevertheless be under no illusions of the immense scale or urgency of these challenges and opportunities – they mandate transformational change across the board. And, as inspirational as the Paris Agreement consensus and mobilisation has been, these conversations and the need for collective actions go well beyond the climate discourse. This is because the science is irrefutable: we have already crossed 3 of the boundaries in the Earth-system (namely, Climate, Biodiversity and Chemicals). These boundaries and tipping points are interconnected, such that crossing tipping points in one boundary may result in irreversible feedback loops in others. This is increasingly evident in the natural world (e.g. coral reef bleaching), meaning that ‘solutions’ for the Anthropocene require new, ecological system-thinking based approaches.

Further, we know that these are not questions only for economics or science alone, but ones that require multi-disciplinary thinking and collaborative efforts: how can the law, economics, science, policy and governance frameworks collectively respond?

For the law – as my own specialism – this discussion invariably also raises eyebrows in some quarters – much similar to those Kate has encountered in the economics field over the years. Legal certainty, clearly, is not for fun – so how can regulatory frameworks be designed in a manner that is capable of responding to updated scientific understandings of ecological systems whilst, for example, still respecting crucial requirements for legal certainty and human rights? These are questions that leading academics at the forefront of the field have been grappling with for a number of years now in view of the Planetary Boundaries discourse. The answer in short: yes, they can with a little thought – and indeed, must if we are to respond to the challenges of the Anthropocene epoch.

These emerging developments in international scientific and cross-disciplinary thinking increasingly make “Brexit boredom” (as a cab driver aptly described it the other day) and the current UK political mantra about “bringing Sovereignty home” all the more ironic. The (wilful or ignorant?) misrepresentation of the very notion of Sovereignty – as a matter of international law – to the UK electorate in recent months conveniently fails to mention that Sovereignty includes intrinsic notions of cooperation as well as correlative responsibilities. The UK is not – in legal terms – in fact, an island. This is particularly evident in the field of the environment where activities de facto do not respect man-made political boundaries.

At its very basic, as with all other nation-states – the UK has a legal obligation under customary international law of ‘no-harm’ to its neighbours in relation to activities that generate environmental transboundary and aggregate harms (covering everything from chemical and industrial pollution, through to climate change). As obligations of customary international law, Whitehall advisers may finally be getting the message through to our leaders that these are not obligations which the UK Government – nor any other for that matter – can walk away from, nor trade away. And it is increasingly clear from published negotiating lines that an EU 27 will (rightly) not permit us to do so. Moreover, the rules-based international legal order is self-evidently likewise in the UK's own interests for rather obvious reasons.

The recognition of the need for co-operation in the environmental field is at the very core of the plethora of Multilateral Environmental Agreements under International Law which bind the UK (at present in many instances as both a matter of EU and International Law) and which often provide the ‘how’ of fulfilling broader, at times more generally framed, international obligations.

And whilst the UK Government has now at least committed to ‘save’ existing environmental laws and protections when exiting the EU – progress and common sense at least(!) – there is currently a discernible lack of published detail in its White Paper about the way it intends to plug resulting insufficiencies in existing legislation and address important governance questions and lacunae that will arise. (Though it is questionable whether there are in reality enough lawyers to tackle the impending, somewhat thankless and significantly downplayed immense task ahead of trawling the legislation books – from experience, not one for the faint-hearted!)

Environmental laws – such as the EU Water Framework Directive or Marine Strategy Directive – have increasingly acknowledged the need for more (not less) ‘ecologically aligned’ approaches; for example, in designating cross-river basin districts and management. This is precisely because the environmental challenges facing humanity today do not respect artificial, political boundaries and are interlinked. The Planetary Boundaries framework requires us to go further along this pathway in formulating updated laws aligned to ecological realities; not the opposite.

So during the ‘Purdah’ lull – making its own headlines in recent weeks – one, therefore, hopes that anyone with an interest in this discourse and Whitehall advisers will make some (fairtrade) coffee and reach for a doughnut of the Raworth kind. Recent headlines demonstrate the significant social, economic and environmental consequences – everything from health budgets, to transport, and energy – that failure to do so risks. It is for that very reason that this discourse needs to be urgently placed front and centre at the very highest levels of Government in the UK to ensure joined-up policy thinking and approaches. It is notable that in Sweden, for example, the Climate portfolio is held at the level of Deputy Prime Minister.

While heartening to see the environmental discourse moving up the UK political agenda in recent weeks, we should see this very much as the beginning of the conversation. For the challenges of the Anthropocene, we need more than a new Environment Act as a knee-jerk to manage the backfire from Brexit. It’s time to start a serious, long-term conversation with experienced policy-makers (yes, experts!), think-tanks, academics, NGOs, civil society and industry about designing Environmental Law 2.0. That is, a fundamental, well-considered and measured overhaul to re-align our laws and policies to ecological realities and properly equip regulators for the task ahead. Crucially, also acknowledging that important trade-offs and conflicts may often require to be addressed (such as in relation to biodiversity and renewable energy). However, they need to be made transparently, efficiently, underpinned by robust environmental impact assessments and grounded in scientific analysis and good governance principles. Experience should demonstrate now that these matters are too important to act as political fodder.

And furthermore, rather than seeking to limit debate and quash public participatory rights (as the last UK Government has used its best endeavours to), let’s hope for all our sakes that a new Government on 9th June (of whatever political persuasion) recognises that public participatory rights are not only a matter of International Law. The very purpose of proper public participatory engagement is to ensure that decision-makers are equipped with the necessary facts to do their job well and make sound decisions for the long-term (as recognised, amongst others, in the Rio Declaration).

The UK ‘public concerned’ is not going anywhere: David can (and indeed will) continue to fight Goliath – increasingly turning to the courts as a means of redress for inept, short-term decision-making that seeks to silence its critics and disregards scientific advice and community views – invariably diverting costs and energy that ultimately everyone (including, very often, pursuers/claimants themselves) agree would ideally be better expended on addressing the substantive challenges. There are other means for the UK Government to address legitimate concerns it has about the abuse of public participatory rights. But first and foremost, a new Government should start by respecting international law and implementing the findings of the UNECE Aarhus Convention Compliance Committee, including addressing the long-standing barriers of access to justice in the UK so that access to our courts does not depend only on the depth of claimants' / pursuers' pockets.

Whilst Courts may not presently be the optimal venue to resolve these disputes in the UK, political leaders should be under no illusions that Judges (even so-labelled, 'conservative' ones) have in the past risen to the challenge of delivering remedies in light of new facts and circumstances which they are presented with and discussions about this topic are gaining traction; for example, adapting procedures to fast-track case hearings, to issuing supervisory orders, or orders for mediation. The idea that litigation can be used by Government as a simple delay tactic – to kick the can or pass the buck for the difficult decision – is not one that it would be wise for future Governments to bank upon long-term, nor as any form of enduring strategy.

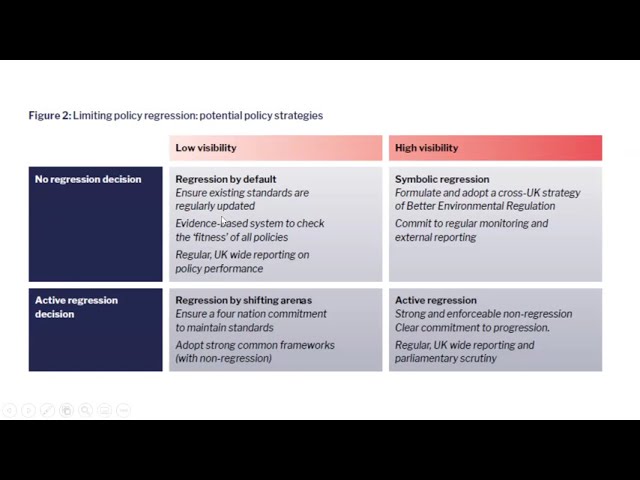

Finally, at the very heart of this discourse after the 8th June needs to be the ‘rule of law’ itself. To embrace the IUCN’s recent recommendations in its World Declaration on Environmental Rule of Law requires our future environmental laws and policies to urgently embrace new concepts and principles such as non-regression, resilience and in dubio pro natura (when in doubt, nature prevails). Whilst many are vocal of the need for investor certainty it should be borne in mind that such certainty comes from the very rule of law itself – and by embracing strategic planning, such as through Strategic Environmental Assessment.

In short, it’s time to flip the paradigm. Let's step up and put Planetary Boundaries and doughnut thinking front and centre, including in UK Environmental Law. The continued failure of all UK political parties to adequately embrace the multi-dimensional environmental agenda and respond to rapidly advancing (international) externalities will only continue to lead one place: before a judge. This must be recongised as a significant barrier and risk to the ecological transition.

Let’s hope that with leadership we can all expend our time more fruitfully after the 8th June. There are promising glimpses in some party manifestos of travel in the right direction!

Susan Shaw is the Managing Partner of Living Law, a public-interest international law firm specialising in environmental, energy and human rights issues. She is a member of the World Commission on Environmental Law, established under the auspices of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. She has worked in Government, the private sector and regulatory roles at domestic, EU and international levels.

t. @susanlivinglaw

Comments